DR. MARY EDWARDS WALKER

AND HER

CONGRESSIONAL MEDAL OF HONOR

c.2005

by

J.W. Cowart

Only 2,639 men -- and one woman -- have won a Congressional Medal of Honor since the award was established in 1862.

Only 2,639 men -- and one woman -- have won a Congressional Medal of Honor since the award was established in 1862.

The nation's highest honor for heroism is "awarded to those members of the Army who distinguish themselves conspicuously by gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of life, above and beyond the call of duty, in action involving actual conflict with an enemy".

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker was the only woman to win this award.

How she won her medal, lost it, and received it back again makes for an odd story:

Her war, like all wars, was terrible.

"Men fall around us like leaves in autumn... The dead are lying everywhere; the wounded are continually passing to the rear; the thunder of the guns and roll of musketry are unceasing and unabated until nightfall... All along the road, for miles wounded men were lying. They had crawled or hobbled slowly away from the fury of the battle, became exhausted and lain down by the roadside to die... What must have been their agony, mental and physical, as they lay in the dreary woods, sensible that there was no one to comfort or care for them..."

On September 20, 1863, Col. John Beatty wrote these lines concerning the Union wounded during the retreat following the Battle of Chickamauga in southern Tennessee.

Within weeks, the Union and Rebel forces would fight again at Chattanooga, Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge. Close to 60,000 Union soldiers would be wounded, killed or horribly mutilated.

Knowing that his men faced near certain chances of being wounded, just a few days before the retreat from Chickamauga, General George H. Thomas, Commander of the Union Army of the Cumberland, had taken an unprecedented action.

He appointed a woman officer.

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker became the nation's first female officer serving as a contract surgeon while holding the rank of First Lieutenant with the 52nd Ohio Regiment.

Even though the need for qualified surgeons was great, the Army Medical Director and the men of the 52nd Infantry protested her commission.

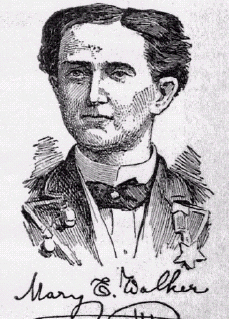

Not only did they object to the rarity of a woman doctor, they especially disliked Mary Walker because she refused to wear a dress.

Not only did they object to the rarity of a woman doctor, they especially disliked Mary Walker because she refused to wear a dress.

She insisted on a modified male officer's uniform including pants with gold piping and tunic. Her preference for masculine-style attire kept her in trouble. In later years, police arrested her several times for "impersonating a man" because of her pantsuit.

General William T. Sherman raged at her, "Why don't you wear proper clothing? That toggery is neither one thing or the other!"

However much Sherman did not like her "toggery", he did recognize her ability.

The fierce battles in southern Tennessee produced thousands of casualties. The crude field hospitals overflowed with wounded.

Captain Augustus C. Brown described a typical scene as an ambulance wagon drawn by six mules approached one hospital tent:

"I saw one man with an arm off at the shoulder, with maggots half an inch long crawling the sloughing flesh, and several poor fellows were holding stumps of legs and arms straight up in the air so as to ease the pain the rough road subjected them to".

Brown tells how teams of surgeons performed assembly-line amputations. "In a very few moments an arm or a leg or some other portion of the subject's anatomy was flung out upon a pile of similar fragments behind the hospital, which was then more than six feet wide and three feet high... Heaven forbid that I should ever again witness such a sight!"

Dr, Mary Walker witnessed such sights daily.

Even before she was officially commissioned, she had voluntarily gone on to the battlefields south of Washington,D.C. and brought wounded men into a temporary hospital which she had helped set up in the halls of the Government Patent Building. In that endeavor she worked with Clara Barton who later founded the American Red Cross.

Dr. Mary Walker also organized a Women's Relief Association in Washington to help the wives, mothers and girlfriends who came to the Capitol seeking news of wounded loved ones and who were often shamefully treated in D.C.

It seems strange that with all of the thousands of Union wounded in Tennessee to care for that Dr. Mary found time to cross into Confederate held territory to deliver babies and give medical attention to ill civilians. She made numerous excursions into the enemy camp doing supposed humanitarian work and returning to General Sherman's headquarters.

Rebel officers grew suspicious, and in April, they captured her in North Georgia and accused her of being a spy.

Perhaps she was; the month after her capture, Sherman invaded Georgia and started his infamous march to the sea.

The Confederates imprisoned Dr. Mary in Castle Thunder, a warehouse on the bank of the James River converted into a prisoner of war camp for officers. While there she offended Southern sensitivities by refusing to wear a dress. She insisted on her pantsuit and a contemporary article in the Richmond Examiner grumbles, "Among other things, she refused to assume garb more becoming to her sex".

While Dr. Mary upset the Confederates; the Union wanted her back. Only four months after her capture, the two warring governments arranged a POW exchange. For the rest of her life she boasted, "I am the only woman in history who, when held as a captive of war, was exchanged as a prisoner of war for a man of equal rank in the army of the foe".

She was traded for a Confederate Major.

Shortly after her return to Washington, President Lincoln, following the recommendations of both General Sherman and General Thomas, signed the citation to award her the Medal of Honor.

Before the award ceremony could be held, John Wilkes Booth assassinated Lincoln. Therefore, it was President Andrew Johnson who, on November 11, 1865, presented the nation's highest award for valor to the woman doctor -- who wore pants to the ceremony.

The inscription engraved on the back of her medal read, "Presented by the Congress of the United States to Mary E. Walker, A.A. Surgeon, U.S. Army."

Congress of the United States to Mary E. Walker, A.A. Surgeon, U.S. Army."

An updated design of the medal was again issued to her in 1907.

Dr. Mary was only 33 years old when the Civil War ended. She had to decided what to do with her life.

For a while, she worked for a New York newspaper where she claimed to be America's first female reporter. She attempted to return to private medical practice at her home in Oswego, N.Y., treating mostly charity patients. She toured Europe lecturing as a war celebrity. She tried dress designing, promoting what she called a "Dress Reform Undersuit" reputed to be rape and seduction proof.

For a while, she worked for a New York newspaper where she claimed to be America's first female reporter. She attempted to return to private medical practice at her home in Oswego, N.Y., treating mostly charity patients. She toured Europe lecturing as a war celebrity. She tried dress designing, promoting what she called a "Dress Reform Undersuit" reputed to be rape and seduction proof.

Finally she found her calling; she would work for women's rights. She joined the suffragette movement to win for women the right to vote.

She appeared at meetings with Susan B. Anthony, Susana Harris, Lucy Stone and Belva Lockwood, who ran for president in 1884 and 1888.

At first, Dr. Mary's support delighted the suffragettes. But soon they became embarrassed by her.

For one thing, she refused to argue for the Nineteenth Amendment; she claimed women already had the right to vote under the Constitution -- they just needed to exercise that right.

For another thing, she continued to wear pants.

"Her coat from the shoulders to waist closely resembles a woman's ordinary attire, but from the waist downward the cut of both coat and pantaloons is masculine. Her hat is the merest chip of straw," said one contemporary.

In 1875, Dr. Walker was appointed to a Civil Service job in the Treasury Dept. Her female co-workers objected to the way she dressed and barred her from the office.

So for two years, Mary Walker reported to work each day and sat in the lobby of the building doing absolutely nothing. Finally, a guard evicted her. At this indignity, she sued the government for back pay! The Treasury made an out-of court settlement with her for $900, one year's pay.

Her mode of dress made her an easy target for ridicule. One antifeminist columnist pointed to Mary Walker as "America's example of a self-made man". Another called her a "curious anthropoid". Newspaper cartoonists had a field day and police arrested her several times for being a public spectacle.

Her mode of dress made her an easy target for ridicule. One antifeminist columnist pointed to Mary Walker as "America's example of a self-made man". Another called her a "curious anthropoid". Newspaper cartoonists had a field day and police arrested her several times for being a public spectacle.

New York patrolman Patrick H. Pickett arrested her on June 14, 1866. When the booking officer asked her where her home was, she snarled, "Wherever float the Stripes and Stars!" When he asked why she dressed as a man instead of wearing long skirts as becomes a lady, she declared, "I wear this dress from high moral principle; the fashionable dress of the day is not such as any physiologist can defend... It sweeps the filth from your sidewalks; it fastens the lungs as within a coffin and it is an abomination, invented by the prostitutes of Paris and as such unfit to be worn by a modest American woman."

The booking officer let her go.

Once, in Washington, when a dog began barking at her heels, a patrolman noticed her unusual attire, arrested her, and charged her with -- of all things -- antagonizing the dog!

Dr. Mary also antagonized smokers. Whenever she saw a man smoking, it was her habit to roll up her umbrella and swat the cigar or pipe out of the unwitting fellow's mouth.

Even when she was not antagonizing people, she stayed in the newspapers. For instance, she once got publicity by offering to raise money for a tuberculosis sanitarium by cutting off her right index finger for auction.

Having alienated dogs, smokers, feminist leaders and the general public by her outspoken and visible eccentricity, Dr. Mary proceeded to antagonize the government which had honored her bravery.

In a series of confrontations over the years, she was thrown out of the Treasury building, evicted from the Patent Office, and barred from the Capitol Building.

She vehemently opposed the government's popular policy in the Philippines. She publicly called President McKinley a common murderer. In 1901, when Czolgosz shot McKinley, Dr. Mary objected to the assassin's being executed, a stand which cost her much public sympathy.

The government retaliated to her attacks by instituting a special investigation into her military benefits. They stopped her $8.50 a month pension.

This government action gave Dr. Mary something new to pester officials about. She resorted to gadfly tactics, harassing congressmen about dress reform, voting legislation, her own pension, smoking and women's rights.

United States Senators ran into the men's room to hide when they saw her coming.

When the United States entered the First World War, Dr. Mary, along with many other suffragettes, opposed the war with Germany. They argued, "Why should women support the war effort when we're not even allowed to vote for the government which declares that war?"

Mary Walker, like other suffragettes, persisted in calling the President -- "Kaiser Wilson"!

The government again retaliated.

In 1916, the Adverse Action Medal of Honor Board discovered that a clerical error had issued awards to 866 members of the 27th Maine Infantry Regiment by mistake. This discovery prompted a general review of the Medal of Honor list of heroes. The Board claimed to find ambiguities in Mary Walker's status as a member of the Army.

In 1916, the Adverse Action Medal of Honor Board discovered that a clerical error had issued awards to 866 members of the 27th Maine Infantry Regiment by mistake. This discovery prompted a general review of the Medal of Honor list of heroes. The Board claimed to find ambiguities in Mary Walker's status as a member of the Army.

On June 3, 1916, they took away her medal.

Actually they didn't take it away.

They wrote a letter notifying her of their decision and asking her to return the medal.

Feisty Dr. Mary, who was now 83, said in effect: I didn't ask for this medal, Congress gave it to me. I didn't mint it, they did. They gave me the original one and they gave me the new one in 1907. I wear one or the other every day. And if they want my medal back, They can come get it!

Who would have dared?.

In 1917, suffragettes marched on Washington. Police ripped down banners denouncing Kaiser Wilson and dragged demonstrators off in shackles to prison where they had to force feed the ladies. Suffragettes chained themselves to the White House fence and to the office doors of government officials. In the confusion,, Dr. Mary Edwards Walker tumbled down the steps of the U.S. Capitol building!

In 1917, suffragettes marched on Washington. Police ripped down banners denouncing Kaiser Wilson and dragged demonstrators off in shackles to prison where they had to force feed the ladies. Suffragettes chained themselves to the White House fence and to the office doors of government officials. In the confusion,, Dr. Mary Edwards Walker tumbled down the steps of the U.S. Capitol building!

She died two years later as a result of her laming fall.

On June 10, 1977, sixty years and seven days after they took away her medal, the Senate Armed Services Committee gave it back.

Senators Edward W. Brooke (R-Mass.) and Birch Bayh (D-Ind.) co-sponsored a resolution to return Dr. Walker's medal. Secretary of the Army Clifford L. Alexander Jr. restored the Medal of Honor.

In a way, the Senate action was a formality because Dr. Mary never gave up her original medal. She wore it until her death and then left it to the Oswego Historical Society near her home in New York where it remains to this day.

__________________

Thank you for visiting www.cowart.info

I welcome your comments at John’s Blog!

You can E-mail me at cowart.johnw@gmail.com

Return to John’s Home Page

You can view my published works at